Around mid-December a free speech controversy started to make the rounds on the internet involving UnitedHealthcare, the controversial healthcare insurer whose CEO, Brian Thompson, was allegedly killed by Luigi Mangione on December 4. Mangione has been arrested and charged with the murder of Thompson. Thompson’s murder launched online controversies over insurance companies and their practices in allowing medical services to be performed on their clients. Support for the alleged killer has risen across America. Some supporters are helping to pay his legal fees and funding his jail commissary because of the anger against the healthcare insurance industry.

There is an ongoing debate over whether supporting Mangione is glorifying violence or magnifying a problem in the health insurance industry. At least one defense attorney, Joel Cohen, has argued that Mangione may not be convicted if one of his supporters were to make their way into the jury pool on a “stealth” basis.

These debates are the basis of free speech.

Whether supporting an alleged murderer encourages lawlessness or is a symptom of a broken healthcare system is a discussion for another column. The issue at hand is how copyright is abused online, not by the creators using abusive cut-and-paste tactics, but by a broken system that encourages fraudulent copyright claims against users trying to gain traction in a crowded field.

The ongoing debates are protected speech under the First Amendment that generally allows Americans to express their opinions about issues no matter how extreme. The right to free expression has been a fundamental right in America since its founding. Although a guaranteed right under the First Amendment, through the years the courts have imposed limits on free speech while acknowledging the right for Americans to express themselves in freely.

Charles Schenck passed out leaflets during World War I arguing that the draft violated the Constitution’s prohibition against involuntary servitude. Schenck was convicted of conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act of 1917. He appealed the conviction, arguing it violated his First Amendment right to free speech. On March 3, 1919, The Supreme Court in Schenck v. United States upheld Schenck’s conviction concluding that the Espionage Act did not violate the First Amendment because it did not meet the “clear and present danger test.” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes compared the leaflets against the draft to “shouting ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater, which is not permitted under the First Amendment.”

Congress the Digital Copyright Millennium Act (DMCA) in 1998, like it did the Espionage Act. The DMCA protects copyright owners from the abusive misuse of their copyright, also known as intellectual property, by users on internet platforms.

Generally, the use of the DMCA is about protecting the monetary benefits that creators derive from their creations, whether they are music, images, or words. But predatory companies and people abuse the DMCA for financial gain, an agenda or simply to deny people the right to express opinions online.

DMCA Abuse

In its most general terms, the DMCA provides a mechanism for someone to have Google, or any other service provider takedown content that someone alleges through a simple filing that they own the copyright to it and they want the service provider to remove it. Under the DMCA, a service provider has immunity from lawsuits if they act on the request to take down material that someone has alleged that they hold the copyright to the material.

The problem with the DMCA is that the service provider is not required to ascertain whether the copyright claimant holds the copyright. The service provider must act on the request to remove the item once they receive the take down request.

Because take down requests are easy to file online and because the provider must take the notice at face value, rampant abuse has resulted in bogus DMCA request filings.

Although DMCA claims can be filed against any internet service provider, including this publication, Google’s reach through links to websites has brought Google into the forefront of the takedown notices. By filing a DMCA notice with Google, anyone can cause a website to be delisted from Google’s search results resulting in lost exposure to the website, either because of a copyright violation or from DMCA abuse. Google owns Youtube, where a DMCA notice often results in a channel’s demonetization which means the channel owner loses income from their work.

A cottage industry has evolved from the DMCA to issue take down notices. One such company is Link-Busters Anti Piracy based in the Netherlands. The company says that “in a nutshell, we find online listings for titles on piracy sites at scale, then we issue takedown notices to those sites on behalf of our clients.”

As of today, Google has delisted 10.8 billion website addresses as the result of DMCA take down requests. Over 5 million websites have been blocked by Google. Using Google’s transparency tool, we know that 637,928 copyrights owners led to the delisting of the content on Google.

According to Google’s DMCA transparency tool we know that Link-Busters.com accounted for over 2 million of the take down requests received by Google. Since late 2023, the company has exponentially increased its takedown notices to Google, with 50,046,125 issued just on December 23rd, the latest date available. The DMCA company represents companies like Penguin Random House, HaperCollins, Simon and Schuster among other well-known publishers.

Google Takes Action Against Abusive Filings

Google offers examples of take down requests it receives where it explains what the request was and why Google did not remove them. Several of them stated that Google “did not take action on the URLs as there were signals of a potentially abusive webform submission.” Submission form abuse refers to the online form that copyright claimants use to issue a takedown request to Google.

One example stated that the individual filed a takedown request asking for the removal of website links with images about them. According to Google, the “images appeared to be fair use as they were included in articles that criticised [sic] the reporter.” Several of the takedown notices that Google determined to be abusive involved the Ukraine-Russia and Israeli-Palestinian conflicts.

There are several requests on Google’s transparency tool that demonstrate the abuse of the DMCA. For example, a church demanded that an image of its website be removed from a website critical of the church’s practices. In another case, an individual created a website, posted an article that had been previously published by a “reputable news site,” and then demanded that Google remove the article on the news site, claiming they owned the copyright. Google determined that the individual who made the complaint had created the site, posted the article, and backdated it after the original source published the article.

In October 2024, Google won a court case against Nguyen Van Duc and Pham Van Thien for filing abusive DMCA takedown requests. Both men pretended to be representing Elon Musk, Taylor Swift and Kanye West to have T-shirt designs taken down. Both men, according to Google, filed 117,000 fraudulent takedown notices with Google.

Notwithstanding Google’s transparency tools or its litigation against abusive DMCA takedown requests, there are many smaller companies and individuals who lose their work through abusive takedown notices. Companies have little incentive to ensure that the individual making the copyright claim can legitimately do so. For many internet service providers, it simply is easier to take down the content from one individual out of thousands than to expose themselves to infringement litigation.

Although the DMCA requires that a takedown notice include a perjury penalty if it is not submitted in good faith, the cost to challenge the validity of the claim in court discourages many smaller companies and individuals from challenging the takedown request. Recently, takedown notices were issued against creators making fan art of Luigi Mangione, the alleged killer.

The Luigi Mangione DMCA Controversy

Fan art of Luigi Mangione, the accused killer of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thomason, was recently taken down by a DMCA takedown notice filed by someone claiming to represent United Healthcare. Although United Healthcare has been named as the source of the takedown notice, this has not been verified.

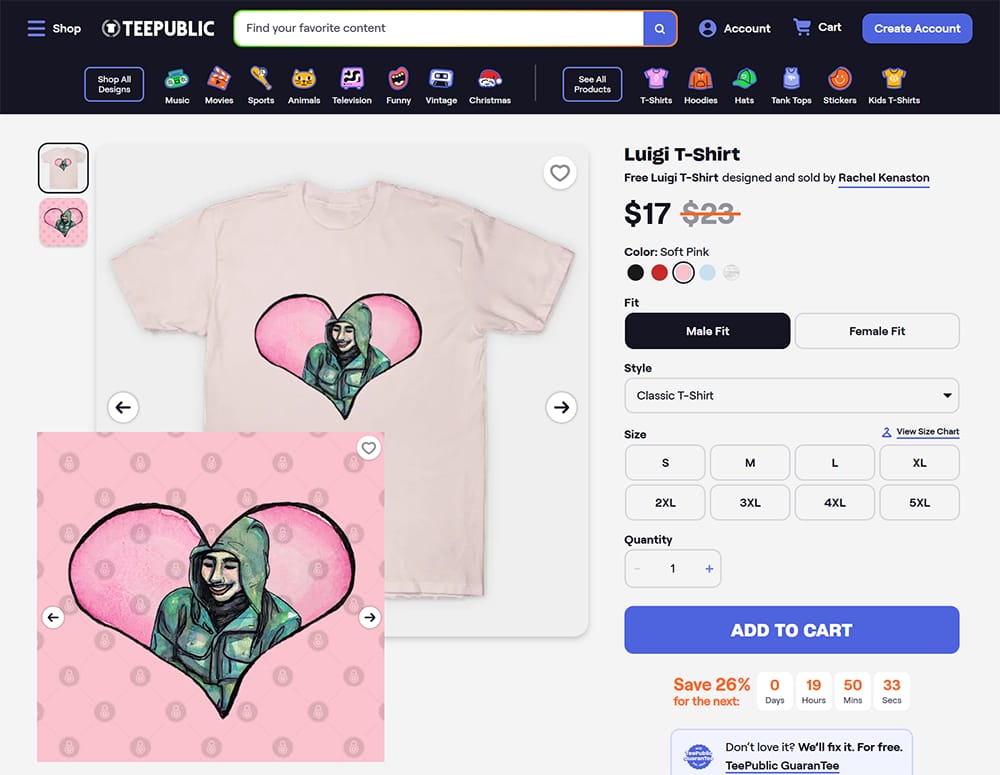

Website screenshot of T-shirt Fan Art

On December 16, Teepublic owned by RedBubble took down Rachel Kenaston’s t-shirt design of Mangione after the on-demand t-shirt company told Kenaston that it received a DMCA takedown request. Kenaston told 404media that “UnitedHealth’s goal is to eliminate Luigi merch from print-on-demand sites,” apparently blaming the health insurance company for the takedown request.

However, the takedown request did not appear to last long. By December 31, Kenaston’s t-shirt was back online.

It is not known if someone representing United Healthcare filed the complaint against Kenaston because of the opaqueness of the process. Although the DMCA has provisions for pursuing frivolous filings, most online companies take the path of less resistance and just remove the material from their sites to avoid liability. The complaint filed against Kenaston is one of many.

But, when a takedown notice becomes viral online, platforms such Teepublic take a second look, which is apparently what happened in Kenaston’s case.

The abuse of the DMCA is so rampant that the Electronic Frontier Foundation has a website dedicated to abusive DMCA practices called the Takedown Hall of Shame. One such case involved Sony who argued it had a copyright over Bach music. Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750. His music is in the public domain and no one, including Sony owns a copyright to it.

That, apparently, did not stop Sony from trying to assert a copyright on it via the DMCA.

It's not just the fan art of Mangione that is being targeted by DMCA requests, but the phrase related to the abusive practices of the healthcare insurance providers is also being targeted.

Along with fan art of Mangione on online t-shirt shops, the use of the term “deny, defend, depose” has seen takedown notices.

Deny, Defend, Depose

The message left at the scene of Brian Thompson’s murder, “deny,” “defend” and “depose” is a phrase that is commonly used to describe how healthcare insurance providers deny medical payments to their clients. The phrase has become a rallying cry for the anger felt by many clients of the healthcare insurance providers.

Although copyrighting a short phase is extremely difficult there is another provision in US intellectual property law that can allow a phrase like “deny, defend and depose” to be protected. It is a trademark.

In its simplest terms, a trademark is a registration of a graphic, logo or a slogan to protect its use for a specific brand use. The key being “specific brand use.” Apple and Nike are some of the most famous brand trademarks.

But, as in the case of Apple, the word “apple” is not trademarked. Anyone can use it because you cannot trademark an isolated word. However, Apple holds the trademark on “Apple” when it is used in conjunction with technology. That does not give Apple the exclusive right to use the word “apple” on everything.

In 1981, Apple settled a lawsuit with Apple Corps, the Beatles’ record company, for $80,000 plus agreeing not to enter the music business. The issue was that the Beatles were using Apple in their music empire before Steve Jobs incorporated Apple in 1977.

The settlement illustrates how trademarks protect words like Apple, for specific uses, which is an important distinction when challenging the use of the word online. Because of the settlement and because the trademark dictates how a trademark can be used, Apple faced two other lawsuits from the Beatles’ record label when it launched its online music store. Eventually they settled but not before Apple paid the Beatles millions of dollars.

The reason Apple has exclusive rights to “Apple” is governed by trademark law under very specific circumstances. For example, we can’t sell computers with Apple on them. But we can sell Apple socks, provided no one has trademarked the name Apple for socks. However, Apple may not let us sell socks unchallenged if they deem our socks could reflect badly on their technology products.

It is the use of trademark that gets us to the phrase, “deny, defend and depose.”

According to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), one individual filed a trademark registration request with its office for the phrase “deny, defend and depose.” There are several other variations that have also been filed.

Michelle Gradnigo filed her application on December 5, 2024, the day after Brian Thompson was killed. The application is currently pending. Gradnigo’s intended use, according to the trademark filing, is for hats.

Gradnigo did not respond to a request for comment for this story as of the publication date. It is unclear if Gradnigo is related to anyone involved in the murder of Thompson or if her filing is to capitalize on the notoriety of the murder.

From experience, it is unlikely that Gradnigo’s trademark application will be approved by the USPTO is it appears to lack the required use in the marketplace example. Generally, a trademark application requires proof that it is being sold before it is granted.

Abusive Automated Systems

For DMCA takedowns to work legitimately and illegitimacy requires the scale of an expensive workforce to file the notices with the different online platforms. In addition to the labor required to file the notices, the website address must be identified, which would require manual intervention to find the material to make the copyright claim.

Because of the scale, both the online platforms and the copyright owners, including the fraudulent takedown request makers have resorted to automated systems to identify and issue DMCA takedown requests.

The use of automation has created an abusive ecosystem being exploited by abusive companies and people.

Youtube, for example, uses Content ID to check user uploads against databases of copyrighted materials like music. When it finds a match, it notifies the user and the copyright holder. If the user has monetized the content, the copyright holder may decide to keep the user’s revenues or have the material taken down. The process is automated on both ends.

In 2018, Google says it invested $100 million in Content ID and paid $3 billion to copyright owners. Copyright enforcement had become a lucrative commodity for both the platforms and for those asserting copyrights.

The fundamental problem with the automation of DMCA takedown notices is that it costs virtually nothing to file them and to defend against them can become expensive. The DMCA is written in such a way that the copyright holder, even the fraudulent ones, “becomes a prosecuting judge” for the material and the defendant has little recourse to defend against it.

To illustrate the problems with the DMCA and its automation, we can look at how the International Olympic Committee (IOC) used the DMCA through its automated system in 2016. Because there was no human intervention, a takedown request was sent to Twitter by the IOC for a post that had nothing to do with the Olympics. The post, which was posted prior to the start of the Olympics, mentioned an athlete by name in an unrelated sporting event, but because the IOC’s automated process lacked human intervention to check the validity of the claim, the post was removed.

Because the DMCA does not require the claimant to provide contact information or respond to requests for additional information, the IOC ignored efforts to clarify the takedown request. Moreover, the DMCA does not provide a mechanism to enforce the requirement to show that the claim is valid because it does not require the claimant to be accessible in the United States.

In the case of the IOC, attempts to clarify the takedown request went unanswered and because the IOC is located outside of the United States, it was “difficult to actually locate and thus beyond the jurisdiction of US law.”

Even if someone is willing to litigate the takedown request, the DMCA makes it not only expensive but difficult, in essence removing the requirement that the plaintiff prove their case leaving the defendant the one having to prove their innocence in a cumbersome and expensive process that is unlikely to result in the appropriate resolution.

It is the automation to reach the scale to be lucrative that has led to abusive practices, with the help of the lack of legal equality the DMCA does not offer.

Weaponizing DMCA

Trying to take someone’s revenues by filing fraudulent DMCA notices, like Sony tried with Bach’s music, is not the only form of abusive DMCA practices. The DMCA has been weaponized. Youtube content creators are aware of how Content ID is abused, but journalists are targeted as well.

In 2022, Mike Burgersburg, a pseudonym used by the author of Dirty Bubble Media was taken down. Dirty Bubble Media was critical about crypto companies. According to the author, his publication was taken down because of “multiple spurious DMCA complaints.”

An unknown malicious actor had registered the domain name unft.news on February 9, 2022. The unknown individual then copied some of Burgersburg’s articles and backdated them. Using the domain name and the backdated material, the malicious actor filed the frivolous take down request and had Burgersburg’s website taken down. The takedown notices were issued by DMCA.com, a company that uses automation to issue takedown notices for $199 to have “content removed from the internet."

The malicious actor had used an automated process that a company has deployed to generate revenues.

The problem, according to EFF’s Katherine Trendacosta who told Mashable at the time, was that “absent a lawsuit,” there “is really no deterrence for sending a bad takedown.” But there is sufficient incentive for the abuse, both in the automated ecosystem that has developed around the DMCA in revenues generated by processing takedown notices to the people who misuse it for nefarious purposes.

Lumen, a database by the Berkman Klein Center at Havard University collecting and cataloging DMCA takedown requests, identified “an organized attempt to abuse copyright law.”

According to Lumen’s research, over the seven-month period between June 2019 and January 2022, they received “almost 34,000 notices that appear to be deliberate fraudulent attempts to misuse” the DMCA.

The targets of the takedown requests were “legitimate news articles and related critical information” that bad actors wanted removed under the DMCA takedown process. The process they used was the same one used against Burgersburg - backdating an article on another site and claiming it as their own.

After sending the claim, the back-dated site is then removed to help cover up their activities. The bad actor targeted Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Russian news sites in “an organized attempt to remove critical news articles,” according to the researcher.

The same technique of backdating articles to have them removed under the DMCA is also used by so-called reputation management companies that promise to erase bad information about an individual from the internet.

The scheme to remove the information that the bad actors do not want online is by first creating a fake news site, reporting a backdated copy of an article and then filing a DMCA takedown request.

Once the DMCA takedown request has been filed, the fake site is removed to help cover up the scheme and to ensure that the targeted material is also removed should the fake DMCA request be successful.

The DMCA was being used to censor critical news reports of people willing to pay to have it removed from the internet. Not just people but oppressive governments have started to use the DMCA to help remove critical news reporting about their governments.

Oppressive Governments Use DMCA To Silence Dissent

In 2018, critical reporting about the Mexican company, Interconecta’s government contract for video surveillance was removed from Página 66. The removal censured the critical article of a company receiving governmental funds.

In Nicaragua, the Daniel Ortega regime used the DMCA to temporarily remove Youtube videos of him making speeches even though Nicaraguan law specifically allowed them to be used under the “public interest exception.”

The use of censorship through the DMCA has been reported in Ecuador and Nigeria as well.

Until American legislators decide that the DMCA abuse has no place in America, the abusive use of it will continue until the law is updated to reflect the abusive reality it has built.